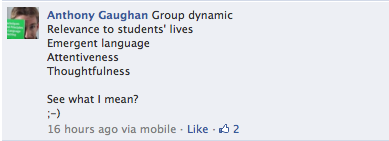

This was the question posed by Mike Harrison on the IATEFL facebook page recently. Considering the space constraints of commenting on a platform like that, and given my Faible for whimsical responses to serious questions, I replied thus:

This was the question posed by Mike Harrison on the IATEFL facebook page recently. Considering the space constraints of commenting on a platform like that, and given my Faible for whimsical responses to serious questions, I replied thus:

If you are familiar with acrostics, a form of poetry where the first letters in each line (or some other regular pattern) form a message, you will see what I have done here – my response to Mike’s question is hiding in plain sight.

But afterwards, amused and satisfied as I was at my minor achievement in melding pedagogy and poetry, I felt the need to expand on this collection of ideas, as I had contributed them with more than simply the intention of showing off my (questionably) witty way with words.

So lI thought I’d look at each of my criteria for what makes a lesson great in a bit more depth over the next few days. I’ll be taking them in order so let’s begin at the beginning with G for Group Dynamic…

Group

Starting from first principles, my dictionary gives the following definitions as primary for defining what a group is:

group |gruːp|

noun [treated as sing. or pl. ]

a number of people or things that are located close together or are considered or classed together : these bodies fall into four distinct groups.

• a number of people who work together or share certain beliefs : I now belong to my local drama group.

What is interesting for me about the first definition is that it applies regardless of whether the individuals in a group actually consider themselves to be constituting one or not. In other words, a group may be a construct defined outside itself.

It’s also interesting that only physical proximity or the practicalities of bundling large numbers of individuals together – possibly to simplify management – are considered defining characteristics of a group.

The second definition is clearly different: it foregrounds cohesion – the bond between the members of the group which defines it as such.

Now, what interests me is that the second definition of a group here is certainly the one I would prefer to apply to groups of students; however, thinking about my schooldays, the first definition – the administratively pragmatic but externally imposed bundling form of grouping – seems to be more descriptively accurate.

Of course, the former type of group can transform into the latter kind given the right conditions – and vice versa! I suspect that getting grouped individuals to sense and invest in a common purpose is a beneficial thing, however, so the question then arises: how can this be achieved?

Dynamic

A word that collocates very strongly in education with the noun group is dynamic. This term gets used a lot by teachers and it commonly seems to mean something like rapport. The classic book Classroom Dynamics is full of activities claiming to establich a positive group dynamic – on inspection, they are mostly predicated on the idea that dynamic is dependent on mutual information and trust – in other words, rapport.

Looking at the dictionary entry for dynamic, we see the following:

dynamic |daɪˈnamɪk|

noun

1 a force that stimulates change or progress within a system or process : evaluation is part of the basic dynamic of the project.ORIGIN early 19th cent. (as a term in physics): from French dynamique, from Greek dunamikos, from dunamis ‘power.’

What strikes you? What I notice is that dynamic is a catalyst for change. It is a change agent, in other words. Its function is to drive systems, to avoid static or stable states.

How is this any different from the idea of rapport? And why is this important? The root meaning of rapport (so my dictionary tells me) goes back to the 17th century French meaning “giving back”; the root for dynamic goes back to Greeek, via French, to the word for “power”.

So rapport is at heart about giving feedback – it is therefore an action more than a state or characteristic of a group, while dynamic is a quality inherent in systems, rather than being an action taken by elements of the system.

Groups are systems, so dynamic is a characteristic of groups, and is a product of rapport. In this sense, then, rapport building is perhaps a poor collocation – we should perhaps be rapport sending, or rapporting – what we are builiding is not rapport, but dynamic, a head of steam. Dynamic is the end, and rapport is the means.

So far, so good… So what?

I thnk this view of rapport and dynamic raises a few questions to which I have no real answers, but think perhaps you might:

- if dynamic is an essential part of a developing system (as development requires change, and dynamic is the change agent), how can it best be generated? Can it actually be generated by teachers at all?

- Can we as teachers really do much to get students rapporting, and thereby building a head of dynamic steam in class?

- In what ways might our current practices be acting as a baffle or impediment to student attempts to rapport to each other?

- Can (and should) teachers seek to steer or leverage group dynamic in deliberate ways? What unforeseen (and potentially detrimental) impacts might this have on the system? How well prepared are teachers in various educational settings to work sensitively with dynamic? Indeed, can this be taught and trained at all?

I think teachers DO have a role in promoting group dynamics as the teacher sets the tone. The teacher’s reaction to the way students interact has an impact!

As always, I enjoy your posts because you get me thinking about things I hadn’t thought of at all. Can you train a teacher a teacher to work sensitively with dynamics? Perhaps by experiencing positive dynamics in the training course, i,e – mainly by example. Hmmm…

Great little poem there!

Thanks Naomi – glad you liked it. I think that “leading by example” can be very powerful, but can we ensure that our examples are accessible? Big question!

I saw your comment on Mike’s facebook post, but didn’t catch the wit. Ah, we move so fast these days that we’re skimming over all the good stuff!

Led a little revolution in my textbook class last week, you’d be happy to hear. Ask the students if they wanted to run the first hour of class every week and then do our “adminstration-assigned” work the second hour AND have a 1/2 of homework, OR just drown through the work as we had the last class where the energy was about the worst I’ve experienced in a long time.

They jumped all over it and we had a good first hour and were directed and more open during the second. Part of my drive for a ‘revolution’ was in all of the discussions we have here, there and everywhere and I want to thank you for driving our GROUP to dig deeper.

Have a great weekend, Anthony!

Thanks, Brad – sounds like there was a powerful dynamic at play there, one which was catalyzed by the choice you offered your learners. Certainly should encourage us all to follow your example more often, I think!

Fascinating and very tough to comment on but I’ll have a go.

I think some classes bond and work due to personalities, some less and some not at all. I’ve heard a shocking number of teachers say “we don’t get on” or “we had a clash”. What this means is that there was no dynamic between the teacher and students maybe due to methods, approaches, style, personality or even something personal. One reason I’ve seen is that the classes in question are sometimes very cohesive and bonded but in a negative way which clashes with what or how the teacher will teach. The result is usually that teachers refuse to teach and have to be replaced. The 2nd choice of teacher is then chosen to be more compatible which often means more relaxed so as to accommodate a more challenging class.

How this class dynamic formed may be the best avenue to study as there must have been a previous teacher or course when the group dynamic was formed. Maybe there was a very tight dynamic/relationship between teacher and students or maybe there was a serious problem between the teacher and students or the students themselves and this created a situation that would pose difficulties for the next person.

Any thoughts?

Phil

Very important point you are raising here – no class exists in a vacuum. The students and the teachers always come to the learning environment with history, and with it, preferences and prejudices. Ways of working, if you will. I have long suspected that when a teacher says “we don’T get on” or “the group has a poor dynamic” it is masking the fact that the teacher either hasn’T really found out what makes the group tick or, if they have, it clashes with how they want to work and they are unwilling to question whether their preferred way of working is actually better than that of their new learners.

I know I have been am?) guilty of such an approach, and of course everyone has a right to decide with whom they wish to work or not, but I suspect that learning how to uncover each others’ preferred and learnt ways of working would be useful. I wonder how this could be done on a teacher training course? I mean, really done, not just talked about in input once in week 4.

Now there’s a question and a VERY important one. After all, a lot of the stuff CELTA/DELTA.. covers is pretty quick and without having the prior experience of say a tough class, then the words of the tutor will mean very little but when you get one you will think back and go “my god, that’s what they meant”.

I think having a first meeting with the class and having a real conversation, not just some NA forms or 121 tutorials.We did this in one place mid and end-of-course and it was very useful. In another we had office hours but it was just the same faces again and again and..I think this is one reason why I always took students for afternoon tea in the first week but I don’t think I exploited it enough. Whereas, with classes I’d taught for a term(s) they were pretty open with me, to the point that I was the one they came to with problems about other teachers.

So, having a mini tutorial with a class to ask what they want, how, why etc might be very insightful.It could even become a project/presentation for week 1 instead of/besides the 121 student analysis.

I’ve been mulling over writing a post called ‘under the surface:what is really going on in your lesson’ but I think it’s beyond me but you perhaps…It would look at on the surface level everyone is ‘doing their part’ ie the teacher is following procedure and playing his/her role and the students the same but underneath there is reticence, growing frustration or lack of interest or on a positive note, enjoyment and appreciation. I don’t think we get enough under that surface when we simply ‘do a lesson’.

Some of my most important career moments have been where I’ve turned a class round or stepped in to help a group/student who wasn’t ‘playing the game’. I did have on student though who resat 2 years of her BA because she refused to play. She was very bright and just found classes frustratingly dull and showed it. Thus, everyone failed her. If she had just ‘jumped through the hoops’ as one tutor said, she’s have got an A.

All great points, Phil. I think your take on the undercurrents in a classroom would be very interesting to read!

Interesting post as usual, Anthony. So, to achieve dynamics, there must first be rapport. Mmm… On my latest post in The Dogme Diaries, I mused, “On hindsight, I suppose I could have got them to do it in pairs, and perhaps that would have made the activity more dynamic…”. I wrote that before I read this post, so it’s got me thinking again.

Perhaps the reason for the lack of dynamics was nothing but the absence of rapport; that the students were still not ready to “give back” what I tried to give them. After all, it was only the second time I’d met them.

OK, so the third time I meet them, I’ll try to work more on the rapport building! Funnily enough, I already had that in mind; only the “how” wasn’t planned yet 😉

Incidentally, could you please modify the link in your blogroll to: http://aclil2climb.blogspot.com ?

Thanks!

Yes, Chiew, your question in your post is based on the dynamic = interaction and bustle metaphor, whereas maybe true dynamic is something that could be felt even in a room of learners working solo, given the right groundwork – let me know who your class develops, won’t you?

And I’m off now to update my blogroll!

Well, I think I meant more than just the hustle and bustle type of dynamics. Interaction has to be present for a class to move ahead, to change and develop according to the needs of the students. It’s much like a child learning a language. Curiosity drives him to interact. It drives him to question everything. Why can’t I reach the chair? Why is it high? Why am I short?

As we grow, we become more afraid to question perhaps because we are afraid to look foolish. So, a class with the right dynamic has students who aren’t afraid of questioning the teacher (or their peers), who aren’t afraid of taking the teacher’s hand (just as a child takes that of his parents) to lead him where he wants to go. And for that to happen, like you say, rapport has to be present. Trust. Confidence…

My third lesson has been reflected upon: http://dogmediaries.wordpress.com/2012/02/03/building-rapport/

Cheers!

[…] Group Dynamic […]

[…] Adobe Flash player to work).Note: You can also read his 5 blog posts by clicking the letters: G R E A T!Related posts: Giving GREAT lessons, part V What makes a lesson great?Share this […]

[…] a lesson GREAT? pt. 1 Posted on 27 January, 2012 by Simon Thomas Anthony Gaughan thinks about group dynamics in ELT classes.Share this post:Bookmark on DeliciousDigg this postRecommend on FacebookGoogle Buzz-up this […]