Float like a butterfly; sting like a bee

– Cassius Clay AKA Muhammad Ali –

Have you ever wondered why you sometimes fail to make a dent on your learners? Why at the end of class you felt like you’d been hitting a brick wall? You had them reeling but you couldn’t knock them out with a piledriver of a lesson?

If you have, then you might – in your darker moments – have thought that teaching might better be left to the Thornburys, the Harmers, the Scriveners – you know, the heavyweights.

But if you thought that, let me tell you that you are wrong. You have all the muscle you need to knock language sense into your learners: you just need to learn a lesson or two from boxers.

You just need to learn to punch your weight in the classroom.

Where a knockout punch begins

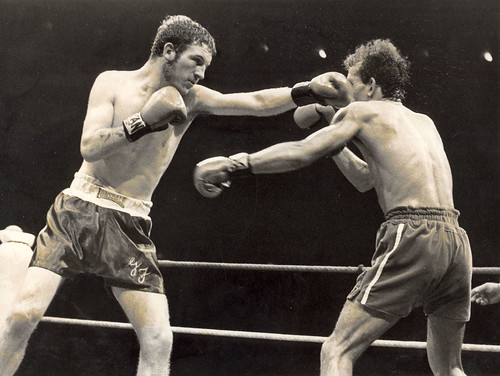

Boxing is a punishing sport which on the surface might not seem to have much to do with the collaborative work of teaching and learning. Get under the surface, however, and you see that classroom practitioners could actually learn a lot from the pugilist. Let me explain.

Anyone who hasn’t boxed might think that a knockout punch is a matter of raw strength but this is not true. In reality, a 50 kilo weakling can knock out an opponent twice their size. That is, they can if they know about:

Timing

Leverage

Targeting

Follow-through

For the remainder of this post, feel free to imagine me in a wooly sailor’s hat, snarling and muttering about “becoming a very dangerous poisun (person)” like Mickey the trainer from the Rocky movies.

Timing

Boxers are masters of timing. They have to be. If they misjudge a feint from their opponent for an opening in his or her guard, they end up on the canvas wondering what day it is. They learn though hundreds of hours of brutal immediate feedback only to react to threat and opportunity where these are clear and present. When the experienced boxer senses their opponent dropping their guard, moving into range or otherwise displaying a vulnerability, they are already putting their body in motion to meet it with aggressive force.

Teachers can learn something from this. If the notion of emergent language and engaging with complex dynamic systems has taught us anything, it is the importance of waiting for, and taking advantage of, the opportune moment. If we react and jump on everything that appears to have potential learning value in our lessons, we run the risk of achieving nothing. Conversely if we keep our guard up throughout classes, dancing about the ring – sorry, classroom – only intent on minimising the punishment we take, then we run the risk of not making an impact on our learners.

Instead, learn to be patient. Spend more time observing and evaluating, noticing when true language learning is emerging from the surrounding language use. You might notice this by asking yourself some of the questions relating to noticing emergent language that I suggest in my webinar about what makes a lesson great.

Whatever it is that sends you the message to swing into action, resist the temptation to come out swinging. Because a knockout punch starts from an unexpected place.

Leverage

You might think that a punch starts in the shoulder. Makes sense: you cock your fist close to that point and send it towards your opponent. Punching that way, however, means you won’t punch your way out of a wet paper bag.

A true knockout punch starts, not at your shoulders, but at your feet.

The heels of the feet are cocked off the ground slightly, to keep you mobile. In the moment the body moves into strike mode, the front heel, imperceptibly, moves downward towards the floor. This grounding leads to a transfer of force up the straightening leg, through the powerful lever of the hip. Meeting the core muscles of the trunk of the body, the subtle turning of the hip towards the target that this triggers leads to a massive loading and amplification of force, channeled through the body out via the shoulder. The arm, which unloads as inevitably as a shot from the chamber of a gun, delivers the hand towards the target with the power behind it of a physical tsunami which started building at ground level – compressed into the square inch of the first two knuckles of the fist.

This is leverage: taking a small amount of effort and, through a series of mechanical amplifications, achieving much greater degree of power on the receiving end.

In teaching terms, we will make a much greater impact on our learners and their learning if we can learn some lessons about how to leverage opportunities in the classroom. Naturally, we won’t be trying to meet what our learners say and do with aggressive counterforce, but the basic principles of finding your feet, transferring power progressively and concentrating effort are worth considering.

Finding your feet

When I was starting out in teaching, the classroom kept me constantly on my guard and I came out swinging at anything that seemed like a useful language target. I was tense and overactive. Over time, I learnt that much of what goes on in lessons is merely activity; relatively few of these “teachable moments” are truly productive and worth following through on.

What are their characteristics? One indicator is that learners shift from discussing meaning to considering form – this is what Michael Long called negotiation for meaning, where learners realise a disruption in their communication which they sense can only be solved by attendance to the form of tehir utterances. Though subsequent research (by Prof. Pauline Foster and others), has shown that Long’s posited focus on morpho-syntax does not generally occur when learners talk to each other, it is still true to say that learner positively support each other when communication gets muddied, often lexically, and that these moments are worth taking advantage of.

To do this, they need to be pinned down. As the boxer pins the emerging moment leading to a knockout punch down beneath his or her heel by a suble grounding, unnoticed by the opponent, the teacher can do the same my noting – literally, noting down – such events. This simple act of pinning down a moment in a lesson makes it retrievable later.

Taking note of learner language is an apparently simple job, but it is surprisingly challenging to do well in practice. Classrooms are noisy and messy environments, and capturing accurate soundbites from your learners, grasping in real time where the learning opportunity resides in what has been said, and considering a means of exploiting this with your learners possibly within a minute or two, is hard work.

It is, however, well within the grasp of most teachers I have met – novice or veteran. Like landing a haymaker punch, it is simply a matter of practice.

Transferring power progressively

Pinning the learning moment down is only the start of a chain of actions leading to a bombshell of a learning moment.

After the teacher has nailed the learning opportunity down, they need gradually to move towards their learners’ boundary of knowledge and/or competence in this area, and push beyond it. This needs to be done in a measured way, or else the learners will be overwhelmed; but it also needs to be swift enough to make use of the power of momentum: (s)he who hesitates is lost.

Beginning teachers often fall into one of two camps when it comes to approaching learner language: either they are too cautious, or they are too eager.

The former group might be able to capture useful language from learner output, but are so hesitant and unconfident in engaging with learners about it that focus and assurance suffer and the potential benefit is lost.

The latter group is too swift in trying to make the learners see the point, and forget that what may seem obvious to the teacher may be less so to the learner. So the teacher rushes, often with a great deal of teacher talk and little learner engagement or checking of understanding, and in the end nothing is achieved.

Somewhere in the middle is the sweet spot where the teacher, working from a concrete example salvaged from their notes, helps the learners re-inhabit this classroom moment and relive this language for a second time. In this more considered re-experience, the teacher uses exemplification, explanation, enquiry and elicitation to raise the learners’ awareness above the plane of the concrete example to the wider horizons of the generalisable pattern. This work may take minutes or it may take moments, but either way, it will be powered by a steadily increasing accumulation of effort and focus.

Concentrating effort

Speaking of focus, it isn’t true to say that a boxer hits with his or her fist; they hit with the first two knuckles. This area, less than one square inch, is where all the accumulated and amplified force of a punch has ended up loaded, waiting to unload on an unsuspecting target.

Teachers have a similar job of concentrating effort to do. Instead of physical effort, the job for teachers is to move their learners’ attention and mental effort from the specific example mentioned earlier to the more general patterns underpinning it. In this abstraction there is a converse condensation of effort – the more a learner needs to generalise from an example instead of simply memorising it as given without alteration or variation, the more cognitive effort they need to invest.

Memorisation, while challenging, is in a sense an unintelligent act – it does not require much reason, abstraction, logic, or other higher order mental effort. So learning the chunk “it’s not the sort of thing that you think would ever happen to you”, while long, is cognitively little different from learning the words “uppercut” or “left hook“.

In contrast, learning that there is a powerful pattern with several variable slots underpinning that fixed expression that can be manipulated and exploited takes real concentration and focus before learners can generate the following:

He’s not the sort of person that you think would ever do a thing like that

It’s not the sort of event that you think you would ever want to go to

They aren’t the sort of questions that you think you would ever need to ask

We will not always get this work of concentrating and focusing on language right, as this candid and perceptive recent post from Hugh Dellar shows. His conclusion that “more os sometimes less” is, I think, in line with the idea of looking at less language more carefully, thoroughly and intensely in class.

Targeting

If you have ever tried to knock someone out, you will know that it isn’t as easy as it looks in the movies. It is incredibly hard to do it with a straight punch to the chin because the chances of making sufficient contact on such a small area are low. A safer option is to come in from the side, and seek out the larger area of the side of the jaw. This is why the uppercut is such a difficult shot to get right, and the left hook is the weapon of choice for the knockout-meister.

In teaching terms, what would such targeting look like? In the post by Hugh Dellar I just mentioned, he identifies some principles worth restating here when approaching lexis:

- target the language in the context learners encounter it first

- then work out towards related parts of speech/grammar patterns within that context

- then work on to conceptually related uses of the word

Follow-through

A knockout punch does not stop when the fist meets the jaw. Anyone who has seen Mike Tyson or Smokin’ Joe Frazier delivering the definition of a jaw-breaking uppercut knows what I mean here: the fist continues travelling through the target, or at least tries to do so. The idea here is that impact is a result of pressure plus speed, and this entails force moving through the target.

Failure to do this in boxing is known as pulling your punches, which is where we get the idiom from. If you as a teacher also want to make an impact, you need to learn not to pull your punches, and follow-through on learning.

In class, this might mean:

- creating short and simple practice tasks to take advantage of learning arising from an unplanned correction

- returning to an earlier teaching moment later in a lesson to check retention

- returning to an earlier learning moment in later lessons to check longer term retention

- deliberately building recent language into future course material and tasks to provide regular and spaced opportunities for re-encountering the language

You’re OUT!!!

This post has already gone 15 rounds and the final bell is sounding loud and clear. Well done for bobbing and weaving through this all – I would love to hear your comments on it.

But as this is a boxing-related entry, I can’t help but leave the last word to a boxing icon, who has some wise words about the fact that it isn’t only about the impact we make on our learners, but how relentless we can be in moving forward in our pursuit of their development.

—–

All still images were sourced with Creative Commons licences. Rocky trailer can be found on YouTube-

[…] Ever got the feeling that your teaching doesn't have the impact on your learners that you would like? Want to knock them out with your teaching? Maybe you need to learn a few lessons from a boxer…. […]

I was looking forward to a picture of you boxing, especially when I read:

“If you have ever tried to knock someone out, you will know that it isn’t as easy as it looks in the movies.”

So, this is what failed candidates get then? You could add a “face or gut?” option.

I think you could also add ‘reaction’ to the list. If you agree with Newton’s theory that every force has an equal and opposite…then every punch that you through comes back at you. A ground puncher can take it back down if relaxed. Same for throwing it out but add tension, poor structure and bad timing and you are literally hitting yourself. I guess in teaching terms we could refer to this as negative feedback or how what and how we teach affects what happens next and what we need to do.

I also like your reference to all body power/punching. Very dogme i.e.using all our tools and skills. This seems to be the style of Klitschko I think. He really uses his body to attack with. He doesn’t just lean back and punch. This explains the ‘punching from the feet’ argument. This is what I see in the lesson descriptions in Chia’s teach-off. She uses everything at her disposal whenever is needed and is not restricted. You get a taste of what she can (style) do but never everything. She never just does tricks or set activities instead she’s teaching with an overall approach or rather ideals/beliefs so everything is free game.

Oh one more is the infamous one inch punch. How does it work, does it work etc may still be mysterious but in theory it is the whole body movement done in a very quick time with little external movement, allegedly possible from any part of the body. Probably why bowers don’t have many friends. Now that could be a quick warmer to activate brains, a snapper grammar explanation or something that is snappy, powerful and has an impact on the class. Of course, if you can knock all the tables out of the window with your little finger that may work too.

I have rambled too long perhaps. Great post and a good excuse to talk about boxing, cricket may not have had the same impact, or maybe it would.

Phil, I am so glad that someone out there understands me 😉

I could have gone on about the lessons we could learn from boxers all day – and very nearly did – so I definitely see where you are coming from with your point about reaction.

I’m fascinated by the parallel you draw with Chia’s work – you make her sound like an MMA fighter! I do like the idea of teaching as being a bit like MMA in that it is a constant search for the most effective combination of techniques in the light of the person you are engaging with within a no-holds-barred environment defined by space (the room) and time (the lesson period). Of course, in our octagon, no one gets hurt, I hope!

And the analogy of the one-inch punch with snappy attention-getters is wonderful. Reminds me of a simple question I asked in a lesson recently that kicked off an incredibly interesting discussion amongst the learners. It doesn’t take much, just timing, leverage and impact.

As for cricket, I might leave that one to you; at some point, though, I might follow this up with something on what we can learn from fencers – especially the notion of the conversation of the blade.

Thanks Anthony for bringing another thought provoking blog post. Your analogy is really convincing in the sense that ,at times, we, the teachers find it so difficult to make any substantial impact on our learners that we tend to frustrate but you have very aptly suggested that we should hit the iron when it’s hot.

In the world of boxing, a well-timed and a targeted punch does enable you to knock down your rival, but in the world of cognition where it’s all abstract, it’s so difficult to control the situation as the learners’ minds (imagination) can fly in any direction and you (the teacher) may end up with a failure.

However, i still appreciate your efforts to help us shoulder our responsibilities.

Thanks Kalim: you are right to point out the limits of the analogy. In a way, though, this is also true in the ring for boxers – their opponents don’t often just stand there as target practice!

And like boxers, we teachers may have days when we swing many more punches than we land. In the end, though, if we keep swinging, we might still win on points 😉

But you could say that teaching to a plan is just delivering something just as practising with a bag or a wooden man is. Without a plan is like fighting a moving, thinking target. You react, fight back, move, dodge…and go with the punches to wear them down then BAM! Break time.

I think that’s quite a fitting analogy to make, and one which also works with the slightly less combative parallel of dancing. You can practice your moves or plan them out as much as you like in advance, and this is of course helpful and in some cases necessary, but in the end it is the person in front of you that you have to dance with and simply going through the motions will not get you another dance with that person, or – back in the ring now – will land you on your back wondering what hit you when you were just following my game plan.

Of course, boxers are in the business of dominance and intimidation: if a boxer succeeds in imposing their will on their opponent, the match works out well for them – but not for their opponent. Equally, perhaps we could say that imposing a plan too forcefully on a group of learners, however committed the teacher may be to the validity of the lesson content or approach, may be good for the teacher but not for the learners?

Pre-planning down to the minute really is a waste of time. I’ve been doing 121s non-stop for a month and each one is slightly different. It’s impossible to plan every one. We work on student choice, reflection and my support. Really useful.

[…] language teachers can learn from boxing Posted on 15 July, 2012 by Simon Thomas Anthony Gaughan applies some principles of boxing to dogme-style language teaching.Share this post:Bookmark on DeliciousDigg this postRecommend on FacebookGoogle Buzz-up this […]

I never thought I would read an anology between boxing and teaching (though I did read on on lion taming, but that’s a different ball game). I couldn’t have imagined any of the points you brought up because I was too repelled to take an interest in what I found difficult to call a sport.

This was fascinating.

While your being an unplugged advocate certainly comes through I think there’s a lot relevant for all kinds of teacher’s. Even teachers using coursebooks modify their teaching according to the student they are “dancing” (as you say in the coment section) with. Seems I’m still having trouble with the boxing anology. It works when I read what you wrote but I keep getting stuck on the following. its a horrible thought to think of a teacher “fighting” with a student. such a thing never ends well. I know, I’ve made that mistake.

Thanks for always making us readers look at things differently!

Naomi

Thanks for reading, Naomi. The analogy is certainly limited and it is hard to separate the useful parallels (as I’ve tried to do here) from the fact that boxing is violent and education should not be. I can well understand how unwelcome such a parallel might seem at first glance, which is why I particularly appreciate your giving the piece a chance.

Anthony

[…] Float like a butterfly; sting like a bee – Cassius Clay AKA Muhammad Ali – Have you ever wondered why you sometimes fail to make a dent on your learners? Why at the end of class you felt like you’d been hitting a brick wall? […]

[…] If you have, then you might – in your darker moments – have thought that teaching might better be left to the Thornburys, the Harmers, the Scriveners – you know, the heavyweights. But if you thought that, let me tell you that … […]

[…] not the sort of thing that you think would ever happen to you” in my last post about punching your weight in class). Beginning teachers need to get good at working on all of these levels, and the sooner they […]